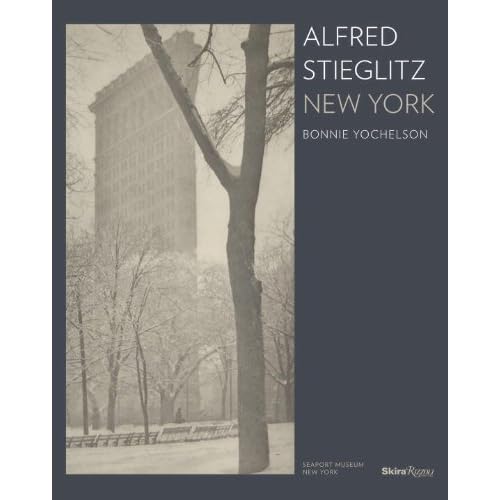

In a weeks time a major retorspective of Georgia O'Keeffe will visit Munich. O'Keeffe was Stieglitz's second wife and some of his photographs, together with those of Paul Strand and Ansel Adams will accompany the exhibition. Anticipation of this exhibition led me to reconsider Stieglitz and in particular a book I purchased a year ago that collects together photographs of New York. Stieglitz grew up in New York, apart from a brief sojourn in Germany to further his education, taking many photographs during his time there. He initially set out to perform a very systematic study of the city building towards a broad portfolio of images, however, this never really came to pass and his city photography progressed in a series of stops and starts.

The book looks at three distinct phases in his photography of the city. The first relates to his initial leaning towards the Pictorialists, photographs that have much of the atmosphere of painted work, in a sense an attempt to show that photography could be as much an art form. These photographs form a fascinating record of turn of the century New York often captured in the freezing fog of winter. The second section dwells on a modern fascination, the juxtaposition of old and new, back in the 1910's this was the growing city backdrop of skyscrapers against the aging low storied buildings they were replacing. Stylistically there is no great change that I detect between these two stages. It is in the final set of photographs, taken between 1930-37 and through the windows of his apartment or studio, where a significant difference can be seen in composition and subject. He is clearly influenced by exposure to the cubist movement, something his New York gallery did much to promote. The photographs capture the array of boxlike forms of buildings piled one atop another. By varying the focal length he was able to shoot the same view over again, but with dramatically different impact. These photographs represent the city as an almost abstract place, early morning absenting human activity from the images. There is a stark formalism to the photographs, but also a personal element, these are the views Stieglitz woke to every day. It is this attachment of art to person that makes these photographs special to me.

As my ongoing exploration of the Landscape of Munich continues, Stieglitz's different responses to his city fascinate me. From a very soft almost romantic view, to the hard edged realism of the skyscrapers, these photographs chart Stieglitz's transformation from a pictorialist to the father of modernist photography. I find myself bouncing between these extremes, with the study of the park driving a soft view of the world, contrasting with the very sharply defined study of the Synagogue. Where Stieglitz spent hours contemplating a single shot, I rattle off dozens of electronic captures, shifting electrons from one place to another. I do wonder if anyone looking back on my photography in 100 years time would be able to discern any form of style from my current work, but then perhaps that is the nature of a student versus a great artist.

The book contains an excellent short biography of Stieglitz, looking at how his galleries, friends and loves, influenced his relationship with New York. However, this story also contains a little technical nugget that made me smile. There is a never ending debate about getting a photograph right in the camera versus capturing a scene and making compositional decisions later on with a cropping tool. The purists generally refer back to the golden age of film, when it had to be right in the camera. TOSH (Technical term for I disagree). The first 3 plates in the book show 3 separate prints from the same negative, the first printed in 1907, the final one in the 20s or 30s. The first print was portrait format, the final landscape. The first clearly used half of the available negative, yielding a dramatic picture of a coach and horses driving through heavy snow. The later image provided much more information about where the shot was taken and peripheral figures removed from the initial print. I learn two things from this; cropping is a legitimate process clearly practiced by even the elite of photography, but most importantly that a photograph exists in its time, returning to it 20 years later might result in a very different desired end point that that which existed when it was taken. A photograph once presented to the public carries inside it the intent of the artist, it is always a personal statement. This statement is read in different ways by the viewer, but significantly the artist can revisit that work and modify the statement.

No comments:

Post a Comment